Disclaimer: This post concerns epistemology rather than ontology. Claims are not about what “seemingly physics-independent” phenomena exist, and how they are, but rather concern how we form ideas about such things.

Summary

Our brains, as physical objects, physically create and utilize various concepts - including seemingly “physics-independent” concepts such as morality, selfhood, and the sentience of others. Their physical origins cast doubt on whether these physically-formed, “seemingly physics-independent” concepts truly reflect corresponding supposedly “non-physical” realities.

This doesn’t refute the existence or nature of the phenomena these concepts represent. However, our material construction of concepts implies that these “physics-independent” phenomena, if real, may not necessarily play any role in the construction of the respective concepts. Viewing ourselves as “concept classifiers” clarifies our understanding of how these concepts of seemingly physics-independent phenomena physically came to be.

Introduction

This post makes the uncontroversial assumption that physical reality exists, and suggests the following:

Any “layer” of reality that we perceive as being “over and above” physics, is merely our brains’ interpretation of physical reality (i.e., concepts). They may appear as “physics-independent things” but they are, in fact, part of how our brains process physical reality, and are physically-constructed. Hence, the concepts do not necessarily accurately describe things “over and above” physics.1

This perspective, which may or may not sound trivial, often has more implications than we realize. By understanding it deeply, we can gain clarity on subjects like metaethics, philosophy of mind, and personal identity. This viewpoint doesn’t necessarily disprove dualism, but it does allow us to comfortably entertain anti-realist perspectives as well as question the extent of our knowledge about certain concepts.

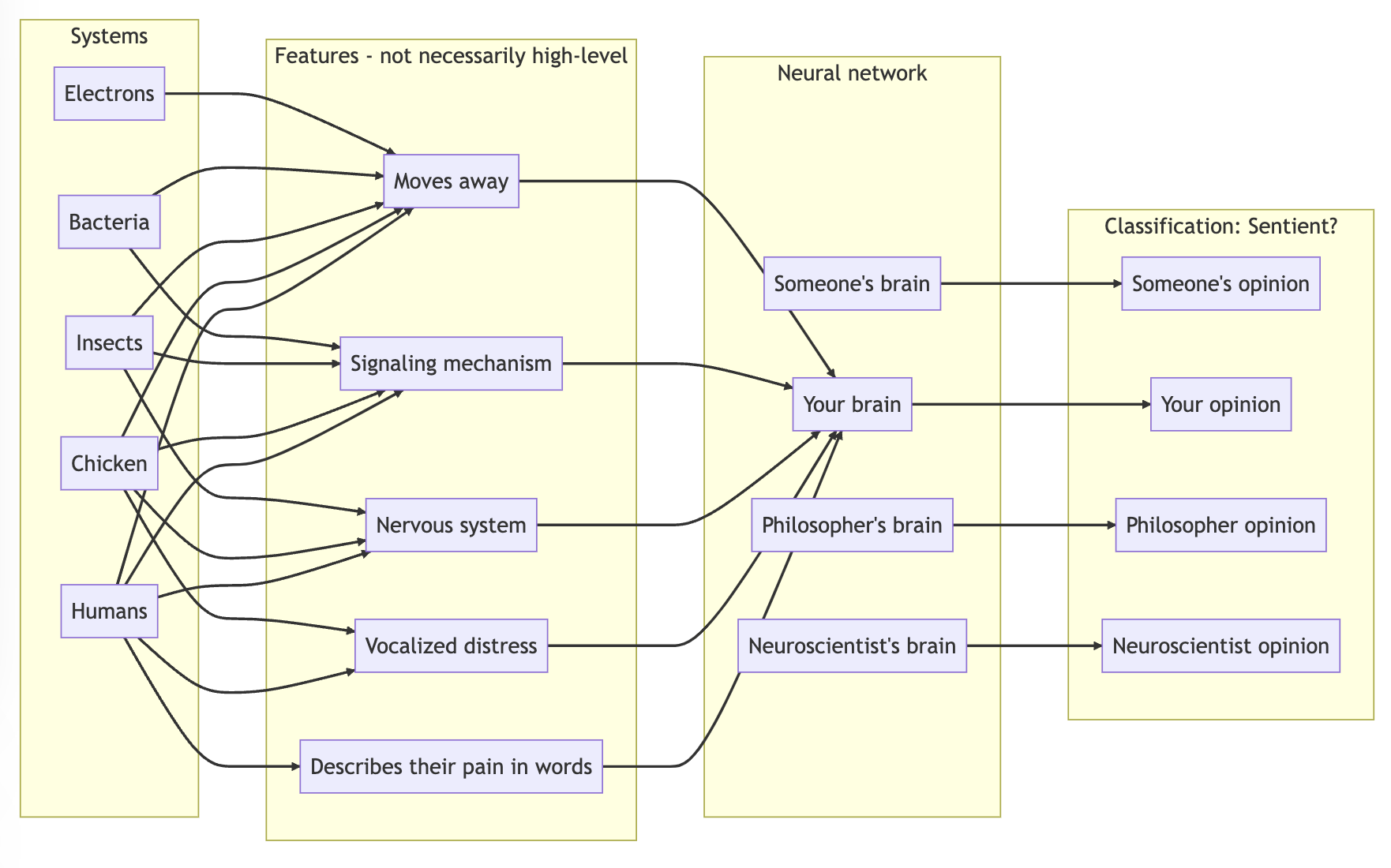

Brian Tomasik’s idea of “sentience classifiers”, processes that may exist in our brains, is helpful for understanding this insight in the context of classifying systems as sentient or not. This “classifier” framework might be generalizable to concepts in other domains. We might term these “concept classifiers”.

Warning: imperfect analogy

Bear in mind that the machine learning analogy and accompanying diagrams are simplifications; they don’t precisely match the biological processes occurring in our brains.2 Differences exist, such as how biological neurons connect compared to their artificial counterparts. Still, these analogies could provide a useful way to grasp how our brains, with “black box” biological functions, process sensory input and result in concept classification. Such mechanisms can be seen as being “trained” through evolution, philosophical reflection, and societal interactions.

Sentience classifier

We classify other systems as sentient or not sentient.

We can think of ourselves as “sentience classifiers”.

- We first attend to a system of interest (e.g. insects).

- We find that it is associated with a bunch of features (e.g. having reactive movement, a signaling mechanism, nervous system).

- Knowledge regarding these features activates parts of a human brain thinking about these things. This information might be assigned high/low importance (analogous to the magnitude of weights), and may qualify/disqualify the system (analogous to the sign of weights).

- Black box stage: some kind of complicated, but in principle, physically understandable, processing happens.

- In the end, a human forms a judgment on whether to classify the system as sentient/what probability to assign to that system being sentient.

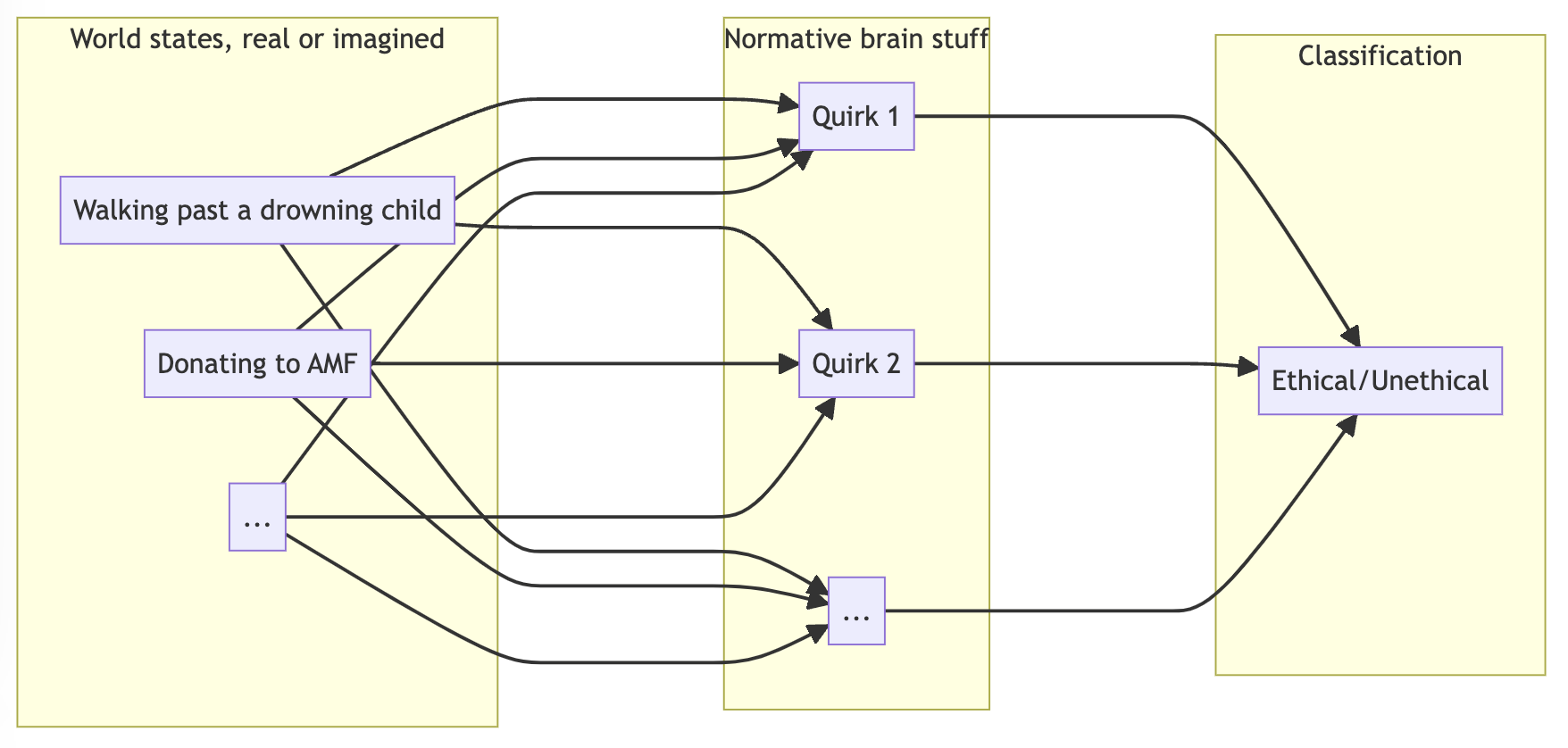

Morality classifier

We classify things as moral or immoral.

Similarly, we might be considered “morality classifiers”.

- We start with world states, real or imagined, with varying levels of detail that may or may not be accurate that provides descriptive information.

- Black box stage: some kind of complicated, but in principle, physically understandable, processing happens.

- We form our moral opinions on it, i.e., is it moral or immoral?

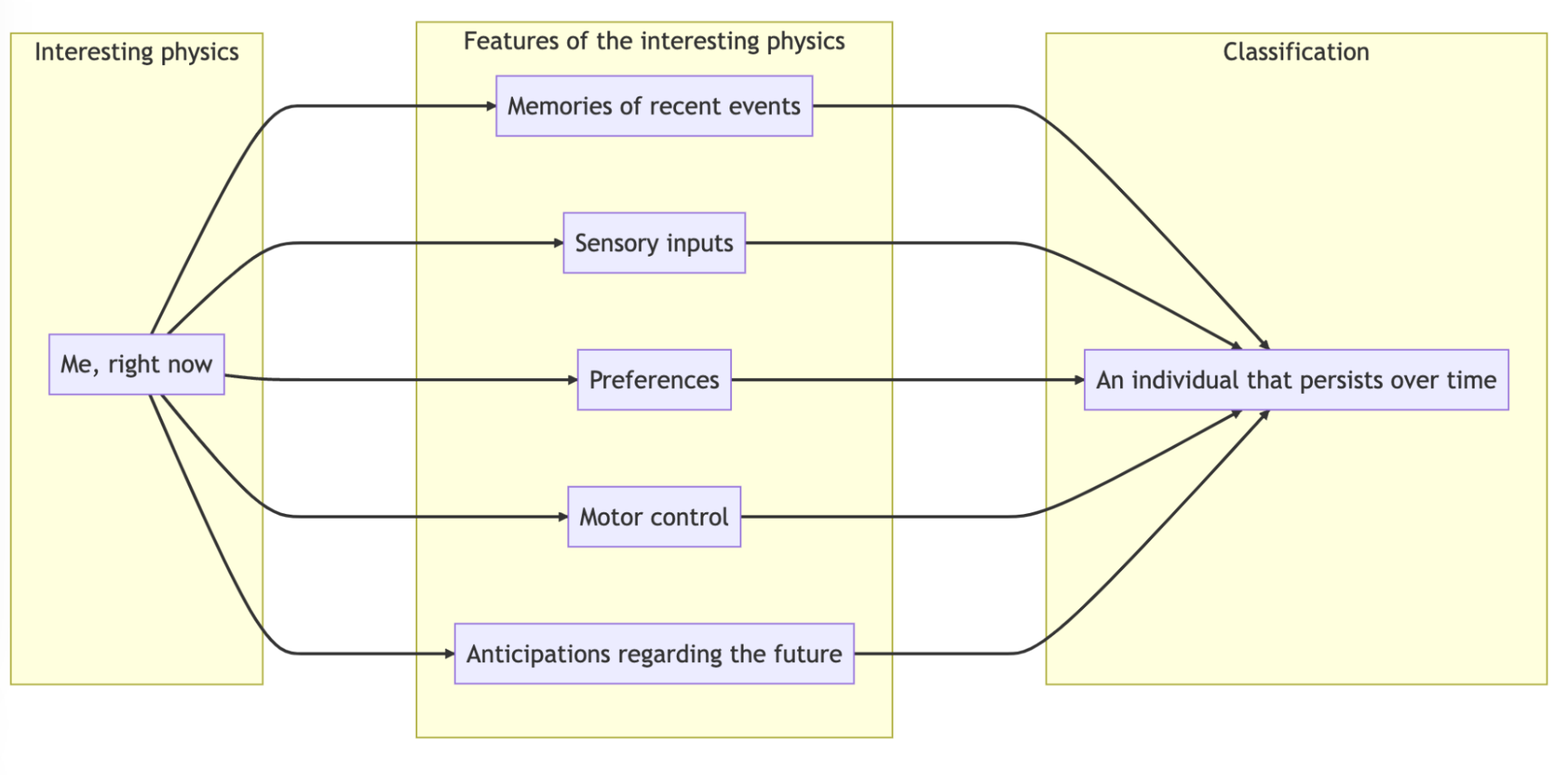

Selfhood classifier

We classify ourselves as individuals that persist over time.

We think of ourselves as individuals that persist over time. This may be an illusion built from various features of the interesting parts of physics that form “us” at the present moment. We might consider ourselves as “selfhood classifiers”.

- There are parts of ourselves linked to a brain that serves a processing center. These parts include: memories of recent events, current sensory inputs, preferences that may be not entirely apparent to us, the ability to control parts of our bodies, and anticipations regarding the future.

- Black box stage: some kind of complicated, but in principle, physically understandable, processing happens.

- We combine those features into a notion of self.

In general, “concept classifiers”

Our process of concept formation (of those that refer to physical reality as well as those that don’t) can be generalized as follows: We receive sensory data from physical systems, which our brains process and decide whether they fit a category. This categorization often results in a binary classification - a ‘yes’ or ’no’ judgment - though there can be exceptions. Some of these classifications, such as those involving sentience, morality, and selfhood refer to things not directly found in external, physical reality. They also feel a lot more significant than other concepts. In essence, this process is “concept classification”.

More classifiers:

As “art classifiers”, we judge visual stimuli, such as a painting, on whether it’s art and its quality. As “mathematical object classifiers”, we can fit sensory data about objects into mental models, or shapes, as well as discern logical relationships between events. Loosely analogous to how artificial neural networks classify image input into “objects”, we might say that our brains too classify sensory data into “objects”.

Training: evolutionary & individual development

How did we get these classifiers in the first place? If humans are using “concept classifiers”, biological mechanisms that process sensory input and classify whether that information should be considered as fitting a specific concept that we use – or not, then it leads to more questions. How are these classifiers “trained”? What constitutes “accurate” classification? How do these biological algorithms evolve?

Evolutionary adaptation could be seen as the initial training phase for our concept classifiers. Instead of gradient descent, biological mutations push the classification algorithms in some direction. Some individuals do not succeed in propagating the genetic code that generates their classification algorithms. Some do. Concept classifiers in a population of a species end up at particular equilibria determined by their evolutionary fitness in a physical environment. Following evolution, concept classifiers are further trained at the individual level (as a human grows up and experiences more). This mostly seems influenced by opinions from society. And for the philosophically-inclined, this is also influenced by philosophical reflection. In short, evolutionary adaptation and various events in one’s life “updates” the concept classifiers in humans.

But are these physical signals about “physics-independent” things reliable? Probably not.

On the population level, successful survival and reproduction, or lack thereof, provides signals that update concept classifiers. It’s crucial to remember, however, that the model’s effectiveness at predicting a system’s physical behavior doesn’t necessarily affirm the existence or nature of “physics-independent” phenomena - such as whether the system has subjective experiences, and what they are. The only requirement is for our concept classifiers to predict external, physical behavior that affects survival and reproduction well. It is perfectly possible that the systems do not internally experience, or do not experience in the way we think they do. Of course, it is intuitively the case that we think they do experience – but this is what we should expect because we are made of predictive models trained as such.

Interactions within society serve as information transmission from one individual to another. Through these interactions, individuals may update their concept classifiers. However, the information has to be true to begin with. If we don’t have real insights, then the updates are not necessarily in the right direction.

Introspection objection

Aside from evolution and society’s influence, our views can be shaped through philosophical reflection. Despite this, philosophical reflection itself is still a physical process. So how do seemingly non-physical phenomena factor in? If we can, in principle, comprehensively explain the process physically, it seems non-physical phenomena do not. This is especially evident with concepts such as morality and selfhood. Regarding sentience, while we acknowledge our own, it’s important to remember that we only directly access our own sentience. As such, our understanding may falter when dealing with systems with significantly different physical processes - perhaps it is the case that, the more different they are, the less accurate our understanding may become.

Takeaway

How we perceive seemingly physics-independent phenomena that exist over and above the physical world, is not necessarily an accurate representation of such phenomena (assuming that they actually exist). This is because we acquired the corresponding concepts by physical means. If the process is, in principle, fully physically explainable, then supposing that “nonphysical” information entered at any point is redundant and dubious. Thus, we should be skeptical that we possess insights into such phenomena (if they even exist).

Thank you to Asher Soryl for insightful comments on a draft.

Relevant reading

How to Interpret a Physical System as a Mind and The Many Fallacies of Dualism

Open individualism - Wikipedia

Notes

-

While this does not necessarily rule out that there are separate entities corresponding to the concepts, a framework that is simpler may exist. Applying Occam’s razor may suggest that we are only left with physics. ↩︎

-

As Tomasik writes: “Something vaguely like this classifier architecture may already exist in our brains—presumably with lots of additional complexities, such as modification of the outputs based on cached thoughts, cultural norms, resolution of cognitive dissonance, etc. Also, the networks in human brains are probably much messier and more computationally complex, have more levels, include recurrent loops.” ↩︎